Not enough movies are set in secluded mountain resorts. They’re environments that are uniquely capable of eliciting emotions like fear, restlessness, and — above all else — paranoia. Emotions, in other words, that form the foundation of any great thriller or horror story. No movie has, of course, ever utilized a mountainside resort as well as The Shining, which uses sinister ghosts and tragic domestic strife to turn a sprawling, mansion-like hotel into a suffocating source of intense cabin fever. Many films since have unsuccessfully tried to replicate that classic’s singularly unsettling effect, but few have truly seized on the brilliance of its setting.

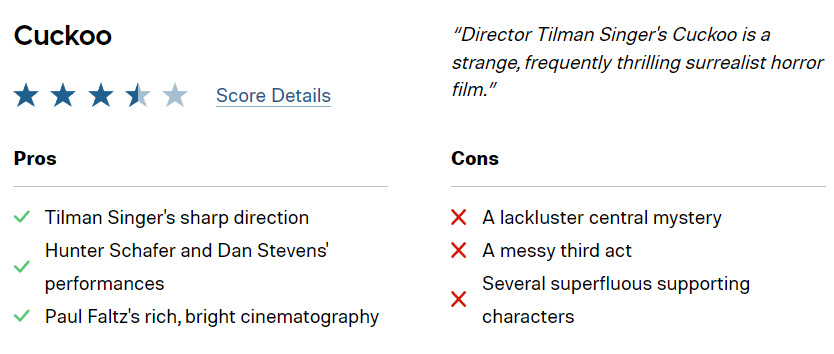

Cuckoo does the latter, and wisely avoids committing the former mistake. It’s an imperfect film where the resolutions prove less satisfying than the buildup to them. The latest thriller from Luz writer-director Tilman Singer is, nonetheless, undeniably the product of a storyteller with an unconventional style and a penchant for capturing the uncanny. Those two talents are employed to impressive effect in Cuckoo, an eerie thriller soaked in paranoia that is greatly elevated by the extremely game performances of its two leads and Singer’s sharp rendering of its central locale.

Cuckoo exists in a world of crooked perspectives and slanted lines — one where shadows don’t just stretch and twist, but also reach toward you. This is demonstrated in the film’s masterfully shot opening shot, where a staircase bannister creates a diagonal line that splits the frame and isolates the bright light from the floor below from the dark interior of a stairwell’s second level. The twisted shadows of two adult arguers are visible in that light. This scene, which is presented in an unusual way, depicts recognizable familial turmoil. Then Cuckoo cuts to an even more unsettling scene: a young girl writhing in her bedroom with pink walls while her hands grip her long red hair, which covers her face and body like a shawl and threatens to tear entire chunks out. The move is so abrupt as to leave you feeling uneasy in the pit of your stomach.

These are pictures of everyday domestic life that have an undercurrent of strange horror because of some crucial framing and blocking decisions. Cuckoo tries to stay on this purposefully off-key note for the whole of its 103-minute running length. Unfortunately, the demands of its mystery box plot keep it from doing so in the second part of the story. In the first hour of the movie, Singer manages to keep both the audience and his protagonist on edge for a considerable amount of the run. He does this while introducing his unlikely hero, Gretchen (Hunter Schafer, star of Euphoria), an angsty adolescent who would much rather be playing music with her band than move with her father, Luis (Marton Csokas), stepmother, Beth (Jessica Henwick), and half-sister, Alma (Mila Lieu) to a resort in the German Alps. To the apparent dismay of both Gretchen and her father, the recent passing of Gretchen’s biological mother has necessitated that she move in full time with Luis and his new family.

Her predicament only gets worse when she meets Herr König (a delightfully hammy Dan Stevens from Abigail), a German businessman whose peculiar demeanor instantly irritates Gretchen. Herr König is also Luis’s boss. Despite her clear distaste for König, Gretchen accepts his offer to work as a front desk clerk at his resort on a paid basis. It is during her first few shifts that she observes odd cases of worn-out women throwing up in the lobby and meets Ed (Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey), a French visitor with whom she instantly wants to flee. Things quickly take an even more nightmarish turn when Gretchen finds herself chased one night by a screaming, red-eyed woman (Kalin Morrow) capable of terrifying feats of strength and speed.

Paul Faltz, a singer and cinematographer, makes the most of Gretchen’s initial encounter with her dangerous stalker. Long, steady pans and tracking shots are used by the pair to create the sequence, which starts by highlighting how lonely and winding the mountainside road is where Gretchen has to ride her bike to get home. Then, in a startling move, they reveal that her assailant has arrived in a shot that cuts from Gretchen’s back to a side view of a row of guest houses in the area, just as a hooded woman storms out of one and begins an abnormally quick sprint. Gretchen’s eyes move from the dark tree branches hanging above her to the shadows they cast on the road, followed by several seconds of pure, dreadful silence from Singer and Faltz. This change in her focus reveals the presence of another, shadowed figure running behind her with its arm outstretched.

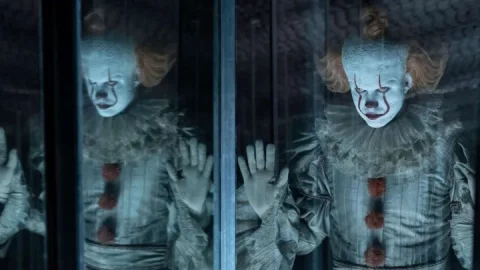

This scene exemplifies a level of directorial control that permeates the entire Cuckoo, one of the most visually striking horror movies of the year, up there with Osgood Perkins’ Longlegs. Singer uses deliberate, frequently well-composed shots to highlight the surreal and beautiful aspects of Cuckoo’s mountainside resort in his most recent work. The spotless white and glass walls of Luis and Beth’s hyper-modern home contrast with the resort’s hotel rooms, hospital walls, and lobby’s aged-wood paneling, which production designer Dario Mendez Acosta used to create an effectively strange and disorienting juxtaposition of old and new. As a result, the unsettling and yet alluring strangeness of Cuckoo’s tale and the barren world are only made more apparent.

The film Cuckoo loses some of its momentum once the true nature of what is happening on the grounds of König’s resort becomes apparent, despite Singer’s skillful introduction of the mysteries surrounding both the strange red-eyed monster and her relationship with Stevens’ clearly unscrupulous Herr König. Cuckoo feels less and less like the high-concept, hallucinogenic horror movie it started out as, by the time its third act turns into a shoot-’em-up, cat-and-mouse chase through a single building. Instead, it feels more and more like a typical action-thriller. The film becomes much less interesting right away when the alluring, otherworldly haze that permeates so much of Cuckoo’s first half disappears. It also shows how flimsy the movie’s plot has always been.

Cuckoo attempts to make up for its lack of depth with flair and style. Schafer and Stevens give performances that are utterly different from one another, and Singer, Faltz, and editors Terel Gibson and Philipp Thomas all give their all to the bizarre concepts and rhythms of the movie. Schafer’s turn is characterized by sharply wound nerves and hardly contained emotions that eventually leak out. She may have seemed to be contributing too much to Cuckoo if it were any other movie, but Stevens’s work both balances and enhances hers.

The latter actor, who has become one of the greatest go-for-it actors of our time over the last ten years, responds to Schafer’s performance’s raw vulnerability with a knowingly evil turn that is both outrageous and precisely calibrated to Cuckoo’s quirky sensibilities. The performances by Schafer and Stevens both elicit discomfort and are uncomfortable. Each of them is putting forth heightened and slightly skewed performance, which is appropriate for a movie like Cuckoo that depicts a version of our world that is both straight and skewed at the same time. Though its durability may be limited, anyone who seeks it out ought to find it difficult to resist Cuckoo’s call at that very moment.

Cuckoo is now playing in theaters.

by DigitaTtrends